If you’re not into Pokémon, this post will seem silly at first, but stick with me; I have a point.

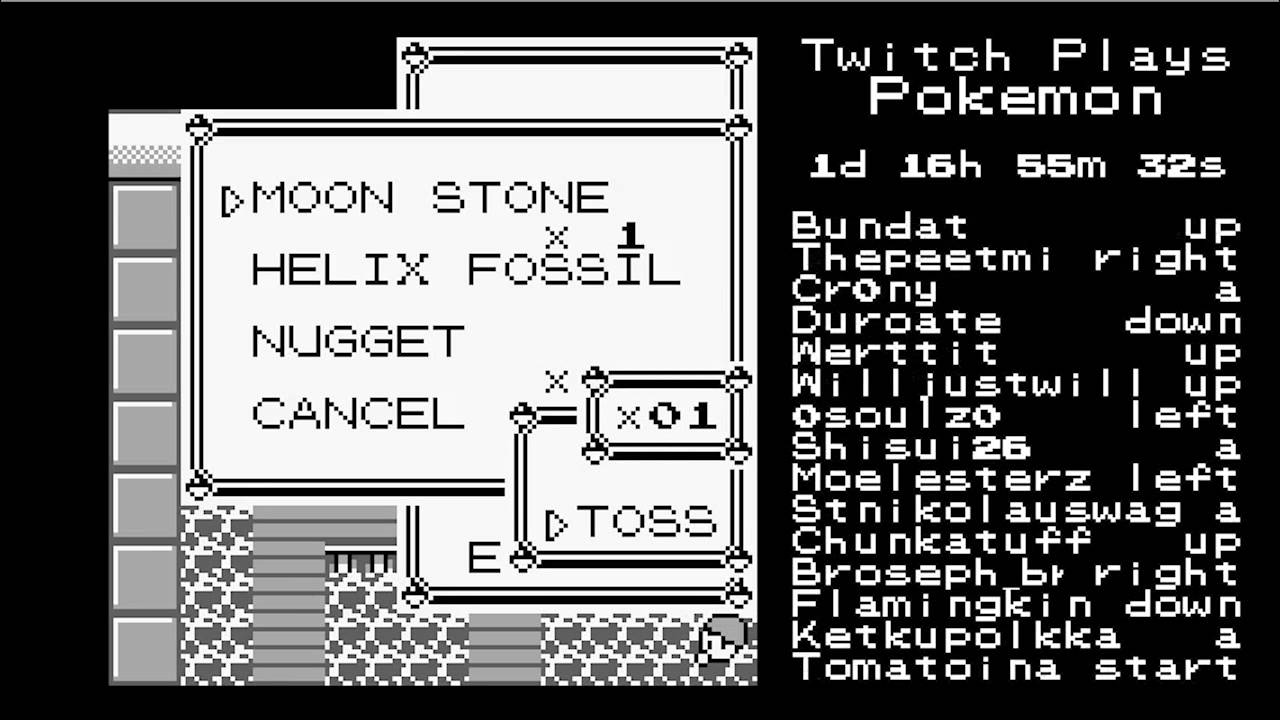

If you’ve heard anything at all about Twitch Plays Pokémon, you’ve heard about the Helix Fossil meme. Before the Helix, though, there was the Moon Stone. Because the Moon Stone was at the top of the item list, and because thousands of people were fighting for control, Twitch kept selecting it; the madness inherent in TPP made people decide that the Moon Stone was some sort of spiritual guide. But the Moon Stone can be tossed. And in TPP, if something can happen, it generally does. So Twitch accidentally tossed the Moon Stone on the second day, just as gaming blogs and websites were beginning to notice the stream. Some arguments followed about whether to worship the Nugget or the Helix Fossil, but then the Nugget got tossed, too. And so the players worshipped the Helix Fossil as a god, and still do.

The funny thing is, the Helix Fossil wasn’t even the item that we accidentally selected the most. A few days in, the Helix Fossil got deposited in the P.C.; although it was quickly withdrawn, the order of items got mixed up, and thus the S.S. Ticket was at the top of the item list far longer than the Helix. Later, the Lift Key was at the top of the list, and thus “consulted” the most often. But neither of those things became “gods”, and the Moon Stone was mostly forgotten about. (Even people who didn’t like the Helix used the Dome Fossil, its counterpart, as their idol, rather than any item we actually possessed.)

Watching the Twitch Plays Pokémon community evolve was like watching the growth of civilization on fast-forward. Yes, it was all kind of a joke, but that doesn’t make it less fascinating. Why did the Helix become so symbolic when it was neither the first item we “consulted”, nor the item we consulted most frequently? Because it was around at the right moment. When TPP’s popularity was skyrocketing each day, the Helix Fossil was at the top of the item list.

Historians have long debated the Great Man Theory of history – basically, the idea that history moves forward due to the actions and decisions of a small number of “great” men. I hold sort of a temporal version of this; I suppose you could call it the Great Moment Theory. Some sort of abstract social energy (for lack of a better term) arises in certain moments – due to a population surge, or technological change, or the fallout of a war, or some other reason. These Great Moments bring about change – change that’s hard to dismantle or rethink until another Great Moment comes along.

I saw several instances of this in Twitch Plays Pokémon. The community often assigned nicknames to their Pokémon, but which nicknames stuck depended on when they were assigned. “Bird Jesus” the Pidgeot was not seen as a savior until four or five days in; and toward the end, Zapdos surpassed him in power. Also, at one point, his in-game nickname was changed to aaabaaajss (if you think that’s a typo, you aren’t familiar with TPP), leading many to call him Abba Jesus; but that didn’t really stick. He had become Bird Jesus during the stream’s Great Moment, when the view count was at its peak, and so that’s what he stayed. A similar thing happened to “Lazorgator,” our starter in Crystal Version; he had moves with lazor-like animations at first, but they were quickly deleted. Still, he had been named Lazorgator at a time when views were around 80,000 (Crystal Version ended with only about 20,000 viewers), so the irrelevant nickname stuck with him for weeks.

Institutions that arise from Great Moments become more powerful when the moment has passed; they carry with them the social energy of a more dynamic time. During TPP’s peak, people tried to keep up with it and organize information in various ways. A popular Google document kept track of the team’s current status, while a live updater reported on events as they occurred. I remember watching, fascinated, as the people in charge of these became vastly more powerful when the view count dropped. Before, the community was so noisy, so productive, that the organizers answered to them; now that the community’s quieted down, they’re practically at the mercy of the organizers. Our Espeon got nicknamed Burrito mostly because that’s what the Google Doc said he was named (weird story). The subreddit was always the most popular place to discuss TPP, but now it’s practically the place to discuss it.

You might think it’s a stretch to compare this to real history, but I don’t. Actually, I’ve noticed the same kind of pattern occur in history all the time. The rise of Christianity was a Great Moment that defined religion in Europe for about a thousand years, until the invention of the printing press allowed for another Great Moment – the Protestant Reformation. China’s philosophical foundation comes from the bloody and dynamic Warring States period. More recently, Google’s prominence comes from its widespread popularity at the outset of the web’s mainstream use; other search engines exist, and are being created constantly, but it’s very hard to compete with something that became a part of people’s lives at just the right time.

This may seem redundant if you think I’m saying “change happens when change happens,” but that’s not what I mean. There are certain moments when change becomes more feasible than other moments – and when we’re not in such a moment, it is very, very difficult to override the change that arose from previous Great Moments. I’m not nearly learned enough in history to know all of the factors that lead to such moments; but I’ve already mentioned population bursts (see: the Baby Boom), technological change (the printing press and the Internet), and major wars (pick one).

What specific change occurs during these moments is largely random. So this isn’t a deterministic view. Still, changing the course of history at the wrong moment – at any moment devoid of a mass societal feeling that it’s time for change – is very hard. Before, I compared this idea to the Great Man Theory. I stick by that comparison. Neither theory requires a clear distinction between the people, or moments, that matter, and the ones that don’t. But some moments clearly matter more than others.